They following text is from a public meeting held by the national Academy of Sciences, Caltech November 2, 3 and 4, 1955.

The Value of Science

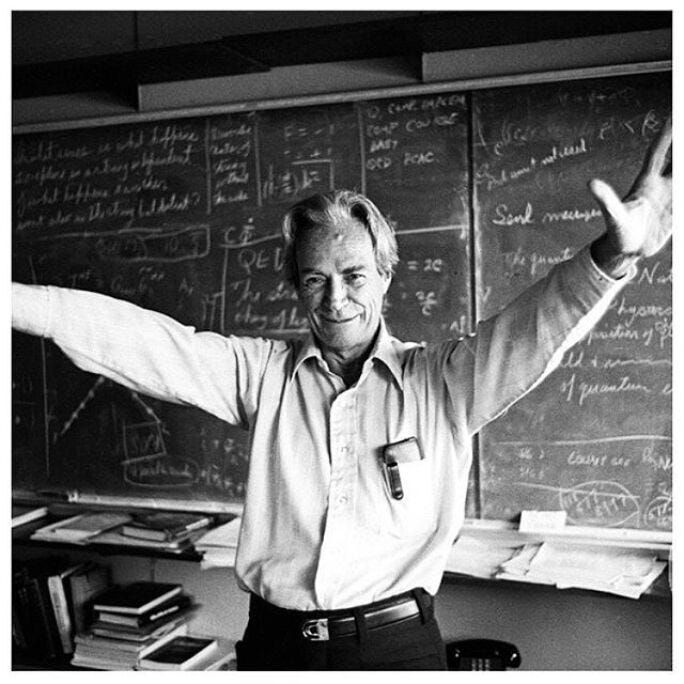

by: Richard P. Feynman

From time to time people suggest to me that scientists ought to give more consideration to social problems – especially that they should be more re- sponsible in considering the impact of science on society. It seems to be generally believed that if the scientists would only look at these very dif- ficult social problems and not spend so much time fooling with less vital scientific ones, great success would come of it.

It seems to me that we do think about these problems from time to time, but we don’t put a full-time effort into them – the reasons being that we know we don’t have any magic formula for solving social problems, that social problems are very much harder than scientific ones, and that we usually don’t get anywhere when we do think about them.

I believe that a scientist looking at nonscientific problems is just as dumb as the next guy – and when he talks about a nonscientific matter, he sounds as naive as anyone untrained in the matter. Since the question of the value of science is not a scientific subject, this talk is dedicated to proving my point – by example.

The first way in which science is of value is familiar to everyone. It is that scientific knowledge enables us to do all kinds of things and to make all kinds of things. Of course if we make good things, it is not only to the credit of science; it is also to the credit of the moral choice which led us to good work. Scientific knowledge is an enabling power to do either good or bad – but it does not carry instructions on how to use it. Such power has evident value – even though the power may be negated by what one does with it.

I learned a way of expressing this common human problem on a trip to Honolulu. In a Buddhist temple there, the man in charge explained a little bit about the Buddhist religion for tourists, and then ended his talk by telling them he had something to say to them that they would never forget – and I have never forgotten it. It was a proverb of the Buddhist religion:

To every man is given the key to the gates of heaven; the same key opens the gates of hell.

What then, is the value of the key to heaven? It is true that if we lack clear instructions that enable us to determine which is the gate to heaven and which the gate to hell, the key may be a dangerous object to use.

But the key obviously has value: how can we enter heaven without it?

Instructions would be of no value without the key. So it is evident that, in spite of the fact that it could produce enormous horror in the world, science is of value because it can produce something.

Another value of science is the fun called intellectual enjoyment which some people get from reading and learning and thinking about it, and which others get from working in it. This is an important point, one which is not considered enough by those who tell us it is our social responsibility to reflect on the impact of science on society

Is this mere personal enjoyment of value to society as a whole? No! But it is also a responsibility to consider the aim of society itself. Is it to arrange matters so that people can enjoy things? If so, then the enjoyment of science is as important as anything else.

But I would like not to underestimate the value of the world view which is the result of scientific effort. We have been led to imagine all sorts of things infinitely more marvelous than the imaginings of poets and dreamers of the past. It shows that the imagination of nature is far, far greater than the imagination of man. For instance, how much more remarkable it is for us all to be stuck – half of us upside down – by a mysterious attraction to a spinning ball that has been swinging in space for billions of years than to be carried on the back of an elephant supported on a tortoise swimming in a bottomless sea.

I have thought about these things so many times alone that I hope you will excuse me if I remind you of this type of thought that I am sure many of you have had, which no one could ever have had in the past because people then didn’t have the information we have about the world today.

For instance, I stand at the seashore, alone, and start to think.

There are the rushing waves mountains of molecules

each stupidly minding its own business

trillions apart

yet forming white surf in unison.

Ages on ages before any eyes could see year after year

thunderously pounding the shore as now. For whom, for what?

On a dead planet

with no life to entertain.

Never at rest

tortured by energy

wasted prodigiously by the sun

poured into space.

A mite makes the sea roar.

Deep in the sea

all molecules repeat

the patterns of one another

till complex new ones are formed.

They make others like themselves

and a new dance starts.

Growing in size and complexity

living things

masses of atoms

DNA, protein

dancing a pattern ever more intricate. Out of the cradle

onto dry land

here it is

standing:

atoms with consciousness;

matter with curiosity.

Stands at the sea,

wonders at wondering: I

a universe of atoms

an atom in the universe.

Share this post